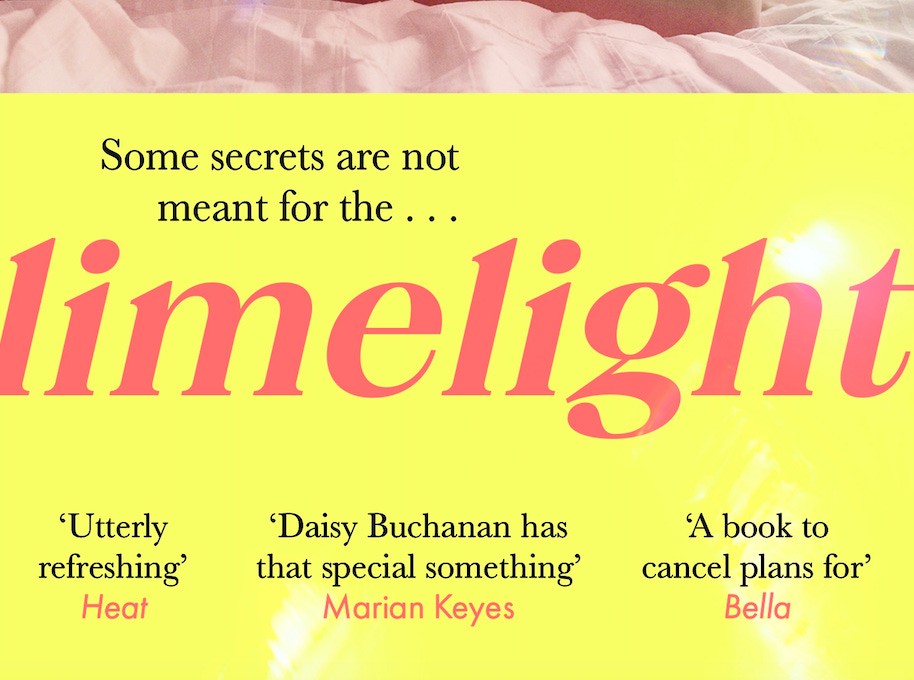

Hello team CCC! I hope you had wonderful weekends, and I’m so happy to be in your inbox. I’m celebrating publication week - Limelight is out on 8 February, and I’m going to be popping up across Substack, on a virtual book tour. I’d love it if you ordered your copy from your local independent book shop - if you do this, I’d be delighted to send you a signed bookplate. Obviously, you can get it from you-know-where, and here’s the link to Waterstones…

This week, I wanted to give you a glimpse into the creative process. I’ve written about motherhood, and what I’ve learned from reading, and writing about mad, bad, sad Mums…

If you’d like to upgrade your subscription, and get full access to the archives, the Sunday Session masterclasses and the chance to post and share comments and be part of the CCC community, I’ve got a special offer on at the moment to celebrate publication week! Click the button below, and all this could be yours…we’ve got a fantastic session coming up with author Kat Brown, and we’ll be talking about creativity, neurodiversity, wearing thousands of career hats, and sharing yourself on the page…

If you’d like to join our gang but you’re not in a position to subscribe at the moment, email creativeconfidenceclinic@gmail.com - I’ll be very happy to give you a gift subscription. And if you’re able to pay for this newsletter, thank you so much. Your generosity means I’m able to share this widely, and spread the word about what I really believe in.

Now, to the mothers…

So far, in every novel I’ve written, there has always been one character who becomes a sneaky scene stealer. This person can’t quite believe they’re not the main character. We’re talking about an extra, who’s extra. This person is a gift, but they come with complicated terms and conditions. A gift because when you show up at your desk and you’re not feeling your best, they will do the work for you – and they usually come up with some stellar jokes. But with one breath, they will promise you that they have an impeccable sense of direction, and with the next, they have grabbed the wheel, they’re holding you hostage and if you don’t concentrate, focus and cajole, they’re going to abandon you in the middle of a field in Somerset, with 90,000 words of nonsense that cannot be corralled into an actual book.

In Insatiable, it was Violet’s boss, Connie – a controlled explosion in a skirt suit. In Careering, it was Imogen’s colleague Louise – posh, wide eyed and weepy, with a killer recipe for millefeuille. In Limelight, it’s Frankie’s mother Allison.

Limelight is a story about why we have such a complicated relationship with attention seeking, and attention seekers. I believe a lot of us identify as ‘introverted show-offs’ – neurodivergent crew, give me a wave! Frankie, the protagonist, feels invisible most of the time. She loves sharing photos on OnlyFans Explicit Online Content Creation Dot Com because it seems like a place where she can seek attention on her own terms. Who she is, and what she does on the website is divorced from the rest of her life, at least in her mind. At first, it’s an outlet where she can let off steam. But why does she seek attention there, but hide from it, when the stakes are higher? Mostly because of her mother.

When I started writing Alison, I knew she was a frustrated stage mother. She has been seeking validation for her daughters, and by extension, for herself. It took me about two and a half drafts to really nail Frankie’s voice, and all of the tensions and ambiguities that lead her to make so many bad decisions. But I found Frankie through Alison. Immediately, I knew that Alison had a lot of uncomfortable, shiny furniture – her cushions would be too full and slippery, you couldn’t sink into anything in her house, you’d bounce off it.

I knew that Alison is vicious, plain speaking and slightly hyperactive, because she’s always starving. She counts everyone else’s biscuits, she lives on scratchy crackers and powdery soup, and she honestly believes that having an appetite for food and sating it is as vulgar as farting. She’s a product of a world that believes women are for display only, and that’s the value she has passed down to her daughters. Alison can seem thoughtless and venal, but she genuinely believes that her way is the safest way. Bean, the eldest sister, has found her way by rejecting every single thing that Alison stands for. For Frankie, it’s harder. Frankie can’t reconcile the truth in her head – that Alison is toxic – with the truth in her heart – she just wants her Mum to love her and be proud of her. Most of all, Frankie is sad because she doesn’t believe her mother can ever be proud of her, because she is a big, tall woman. She will never be a dainty doll. She’s starved for validation, and when she shares photos, she feels feminine. Not in a way that her mother could understand – but in a way that makes her feel good.

A question I like to ask my You’re Booked guests is ‘Which fictional family would you have liked to have been born into? And which fictional family do you think would be the worst to eat Christmas dinner with?’ Everyone finds it easier to think of options for the latter category. Even my beloved Cazalet Chronicles are riddled with mad, bad Mums and Dads. I often think of Villy, and her relationship with her daughter, Louise.

Seen through Louise’s eyes, Villy is cruel, brittle, and totally lacking in empathy. But as we learn the truth about Villy’s marriage, and her life beyond it, we start to see her more clearly. She’s married to Edward the only irredeemable Cazalet villain (but what a horribly charming villain he is!), and she’s forced to leave a career she loved for that marriage, because that was what women were expected to do at the time. Literature is littered with monstrous mothers, and we’re fascinated by them. They comfort us, too. Unless we’re exceptionally lucky, I think we’ve all sometimes looked at the person who has brought us into the world and wanted to know if they could really see us, and really understand us. We ask so much of mothers, on the page, and in reality. We ask so much of women.

In Limelight, I birthed a monstrous mother, and it helped me to understand how my heroine had become herself. Yet I knew, instinctively, that Alison had been a product of her own environment, just as Frankie had. I’m currently in the earliest stages of exploring my own neurodiversity, and I’m struck by the volume of women who have been prompted to discover theirs, through their children. I don’t think I want to become a mother, in real life, and I’m starting to realise why. Deep down, I know I would cope so badly with the noise, the chaos and the relentless overwhelm. But I’ve started to wonder about the ‘bad’ mothers that haunt literature, and how much terrible imaginary mothering is borne out of real-life experience – women who were misunderstood, and not supported, and as a result, became desperate and broken. Alison’s anxiety, her determination to stay in control, her genuine belief that something very bad will happen to her if she has a spoonful of sugar in her tea – not neurotypical.

In literature, and in life, we judge mothers much more stringently than fathers. But books have the power to change this pattern. And any writer and reader worth their salt will be wondering about these mothers. We search for the stories within the stories. We can start to plot and embroider, we can go behind the scenes, and travel in time and wonder what has led these characters to reach the point at which we meet them on the page. If you’re after a writing prompt, try taking the worst imaginary mother you can think of, and write her origin story. (If you fancy having a go at Alison’s, I’d be delighted!)

I can see myself in the bad mothers. I hear scraps of myself in Villy, Mrs Bennett, Pam “Bridget” Jones (who is also Mrs Bennett, I know). And I’m grateful for it. These stories show me what might happen when I don’t make the effort to be kind, patient and occasionally bite my tongue. All useful prompts for this neurodivergent woman.

Elsewhere, I see a lot of portrayals of perfect parents – if you’re a mother in an advert, you must be laughing, leaping, showing off your straight white teeth and shiny hair. Unless you’re trying to sell laundry detergent, this helps no-one. But ‘bad’ mothers in books are usually telling us something true and painful about being human. I’m so grateful that our bookshelves are filled with these rich, layered portrayals of imaginary mothers who are very real, and very flawed. I believe they make me a better writer, and more importantly, a more open-hearted person.

Which fictional mother has made a lasting impression on you? Who are the literary parents you love and hate? Tell me in the comments, I’d love to hear from you! And, if you’re nodding and buzzing and want to chat about neurodivergence, you need to come to our Sunday Session with Kat Brown -find out more here!

Love

Daisy x

I've just finished Such A Fun Age - and I suspect I am going to be thinking about the mother in that, Alix (complacent, self-obsessed, desperately trying to hold on to her old life to the point of neglecting her oldest daughter...), for a long time.

‘introverted show-offs’ omg! I have never heard this term before but boy does it hit home!